Mar 7th, 2014

The TSA process, the Lewisham case, clause 119 of the Care Bill and the new amendments

By David Lock QC

You can also read this blog post on the Open Democracy website here:

http://www.opendemocracy.net/ournhs/david-lock/former-minister-burstow-proposes-softening-hospital-closure-clause

The debate about clause 119 of the Care Bill, which seeks to make amendments to Chapter 5A of the NHS Act, is an example of the government trying to use a screwdriver to undo a bolt. The government have a real problem but clause 119 is the wrong tool to try to solve it.

There is a remarkable consensus across informed professionals who care about NHS services that, in order to deliver high quality care and direct money and staff to patients such as the frail elderly who need community services, the NHS needs to make substantial changes to its footprint of local hospitals right across the NHS. But the NHS is a taxpayer funded service and making changes to the footprint of NHS buildings, let alone closing hospitals, is bad politics. I should know more than anyone because if changes to hospital services in Kidderminster had not been so controversial, I might still be a serving MP!

The problem is that the NHS needs a much better way to take these difficult decisions. But the present amendments to the TSA process are just about the worst possible way to do this. The scheme brought forward by the government is both legally ineffective and is potentially politically incendiary. Even if it worked as a legal scheme (which it does not) it is the wrong solution to a real problem for numerous reasons.

The amendments to be moved by Paul Burstow MP will ameliorate the worst parts of the scheme. This will at least deliver a scheme that is legally effective, but it’s an inelegant compromise where a more comprehensive approach is needed.

The TSA regime was brought in to deal with the exceptional case where an NHS Trust or an NHS Foundation Trust got into serious financial trouble. But no Trust is an island and where there are such serious problems at an NHS Trust that a TSA is a realistic prospect, there will almost certainly be other problems. There may be a dysfunctional relationship with commissioners or there may simply be too many NHS acute hospitals competing for too few patients, with the result that none of them is able to survive financially.

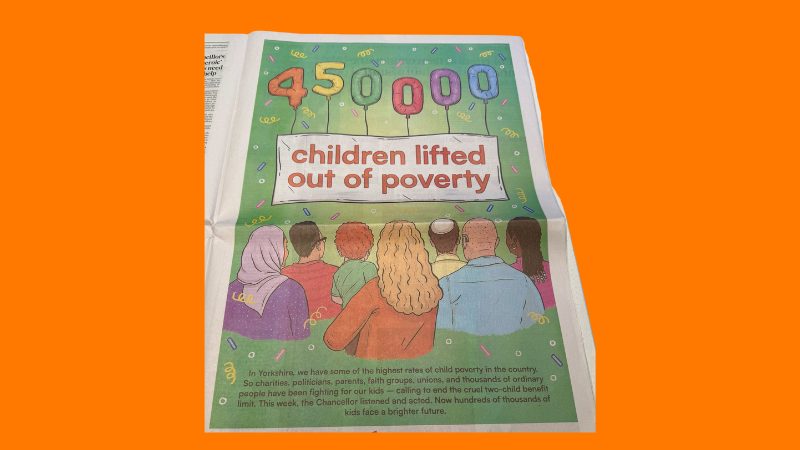

The patient population to support an acute hospital is probably now about 450,000. Hence an area of 400,000 people cannot viably support 2 full, 24 hour acute hospitals, as for example Gloucestershire residents had to accept when deciding whether both Cheltenham and Gloucester could stay open as full acute centres. That was a controversial decision that was made locally after full patient consultation with all the options being examined. For present purposes it does not matter whether the local NHS decision makers were right or wrong. The decision was made locally after a local engagement exercise and thus had a measure of local credibility.

Using the TSA process to impose structural changes across a health economy over the heads of local NHS commissioners and providers is misguided for many reasons. It is a spectacularly wrong solution to a real problem.

First, this is not what the TSA process was brought in to deliver. Chapter 5A brought in the TSA process to solve an exceptional financial crisis in a single trust. Making changes to NHS hospital services across a health economy is not exceptional. Facing up to these difficult decisions is now a routine part of the work of the NHS throughout the country. It is wrong in principle to use exceptional powers to solve routine problems.

Secondly, if the government uses the TSA process to impose changes on a reluctant local health economy it politicises a decision that can only be successfully taken and implemented if it is de-politicised. The government that tries to use a TSA process to impose sweeping change without proper local public engagement will face a unity of political opposition. Nothing unites a community more than having their hospital services removed but imagine the uproar if they are removed for purely financial reasons by unaccountable bureaucrats over the heads of local GPs. Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs might as well give up now because their government will be held responsible for giving the power to an unaccountable bureaucrat to close down their local A & E and they will be punished at the next election.

Thirdly, the TSA scheme, as proposed by the government, is unfair because it gives NHS commissioners of services at hospitals run by the failing trust a privileged position. Those commissioners have a veto on the extent of changes to their hospitals, whereas the commissioners of services at successful trusts have no such right. Thus those in the NHS who have worked hard to create viable, constructive relationships between commissioners and providers will have services removed. A cynic might say that this was an example of the dysfunctional parts of the health economy being entitled to write the rules to disadvantage the functional parts.

Fourthly, the proposed TSA process cuts across the mantra of the present government that commissioning decisions should be clinically led and should be made locally. Under the TSA process these are not local decisions and they are not made by clinicians. On the day after he came into office in May 2010 Andrew Lansley, wrote as follows in a national newspaper:

Bureaucracy and a top-down approach have undermined the health service ….. Patients and clinicians must be put in control. …. It is time we recognised that the real headquarters of the NHS is not on Whitehall, it’s wherever there are patients, it’s the doctors and nurses whom we register with at our local practice. These are the people whom we rely on and trust. They should be the ones making the decisions about the management of our services as well. That is how we will create a service that is centred on the needs and the wishes of patients.

Less than 4 years later we see the government abandoning this approach as it tries to introduce far more centralising powers than Labour ever did. These powers are inconsistent with a clinically led commissioning.

Finally, the TSA process is a failure because of the lack of public engagement. NHS England’s own recent document on public engagement had a telling part which said:

“Evidence suggests that engaging and involving communities in the planning, design and delivery of health and care services can lead to a more joined-up, co-ordinated and efficient services that are more responsive to local community needs. Public participation can also help to build partnerships with communities and identify areas for service improvement. ….

Insight gathered from the public helps to improve services and outcomes as well as potentially helping to spot failures. Listening to and using the voice of patients and the public were never more forcefully presented than in the Francis report”

So why is one part of the NHS suggesting curtailing public engagement when another part of the NHS says that the lesson is that full public engagement is essential to getting these difficult decisions right? The NHS is thus pulling in different directions.

The Burstow amendments will put all commissioners on an equal footing. They prevent the TSA, Monitor or the Secretary of State being the decision maker where changes are proposed in a TSA Report outside the Trust in administration and thus restores the principle of local, clinically led commissioning. It also brings back proper patient engagement before decisions are put into effect outside the Trust in administration. It is not a perfect solution but paradoxically it is one that is consistent with lots of other strands of government policy.

****

David Lock QC was MP for Wyre Forest (Kidderminster) from 1997 to 2001. He was counsel for the Campaign in the Lewisham Hospital case in the High Court and Court of Appeal and was instructed by 38 Degrees to draft amendments to the Care Bill. These are his personal views and should not be attributed to 38 Degrees.